Jesus Wept '

Jesus Wept '

By Dr. Timothy E. Nelson, Historian, Artist, and Professor

Preface:

I began this article with the idea, What Would Jesus Do in Blackdom during Juneteenth. There were twists and turns so I decided to write a preface. Not to say one can’t easily understand the article without an intro to the introduction; but, I am writing this during a trying time (pandemic) in mind and to be honest, it is a privilege to complete a thought.

Why Jesus? Because God was the guest of honor at Juneteenth celebrations. Have you ever realized how amazing your father was after coming out of a time of not knowing the full weight of being the Patriarch? This pandemic has changed America. Many had to find faith. I wondered how Blackdomites, Black then, were still able to maintain and grow after continually suffering devastating losses. The answer; God. And then, Walmart tried to trademark Juneteenth.

Introduction: Blackdom (Town) History (1900 - 1930)

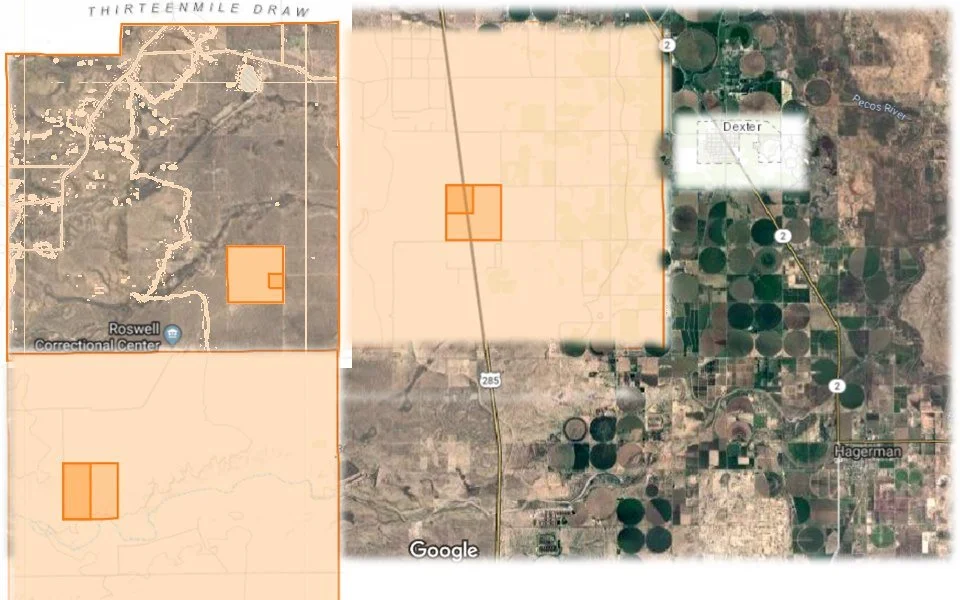

In the early 1900s, the Pecos Valley Region of Southeastern New Mexico; a U.S. Territory at the time, experienced an economic boom because of an influx of settlers into the area. People under the conditions of “Americanized Blackness” became settlers as well. They built Blackdom, the only All-Black Town in the territory. The city of Roswell was 20 miles north, all of which was situated in Chaves County. Today little remains of this ambitious frontier scheme that within a 20-year period became an oil producing town during the Roaring 20s/Harlem Renaissance.

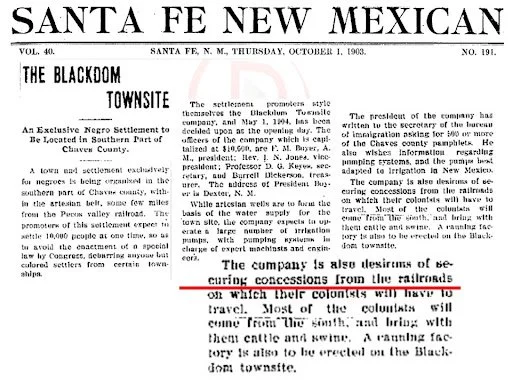

In September 1903, thirteen Black men led by Isaac W. Jones and Francis M. (Frank) Boyer, signed the Articles of Incorporation to establish the Blackdom Townsite Company to build the town. Blackdom was located on a direct route to the Dexter train station to the East, and Artesia, another New Mexico Territory boom town 20 miles south. West of Blackdom was Apache land; however, to be honest, all of it was Mescalero Territory. Colonizers settled and the rest is a long story about genocide in perpetuity.

A few of the early founders were former soldiers in the All-Black 24th Infantry which served throughout U.S. Territory of New Mexico in the 1880s and 1890s. Frank Boyer was the most influential of them having trained as a minister at Atlanta (Georgia) Baptist College (now Morehouse College) following his discharge from the military. Boyer and his wife Ella, also brought Black Freemasonry to the county establishing the first masonic lodge.

An Afro-frontier town relying on dry-farming proved difficult to maintain. Survival depended on rain that often didn’t come. Between 1909 and 1916, however, the rains came and Blackdom was tangibly prosperous. In 1912, New Mexico transitioned into an incorporated State.

Between 1912 and 1915, Black people were sovereign beings with all power to control their tangible existence in “Blackdom.” The significance of statehood on Blackdom was the transfer of power from federal authorities to local district authorities. Blackdomites were sovereign beings on sovereign land led by Rev. Isaac W. Jones and Francis (Frank) Marion Boyer; until, White People.

In 1915, God was the significance of Juneteenth, even though Blackdomites suffered a great loss that year. As an incorporated town, Blackdom was at its peak. Believers understood Juneteenth as their “Day of Jubilee.” All 13 founders of Blackdom Townsite Company were deeply impacted by major and minor institutions of slavery.

In 1917, Blackdom saw many of its young men conscripted into the military as the United States entered World War I. By train, during Blackdom’s Revival (1909-1919), a second cohort of settlers/ Black Colonizers employed their freedoms to migrate with their families out of a “plantation life” to further develop a sovereign space.

In 1919, oil was discovered and Blackdom residents created the Blackdom Oil Company. Blackdom Oil contracted with the New York-based National Exploration Company to drill. In a 1947 interview with Blackdom Townsite Company’s 1st President Frank Boyer, revealed that some Blackdom residents still received royalties from Gulf Oil confirming royalties in the post-WWII era (1945 - the start of the Vietnam Conflict [1955 - 1975]).

God, Blackdom, and Juneteenth

Blackdomites were inspired by the God of Abrahamic faiths to seek Afrotopia. “Blackdom” (the idea) had become Blackdom (fareal, fareal) by 1915 and fulfilled God’s covenant to “Black” People. On New Mexico’s desert prairies, Blackdom produced a tangible Promise Land. Jesus could appreciate the image of people living out his father’s promise. At Blackdom during the Juneteenth celebration, there was no Henney. Just Say’n. Blackdomites may have had wine. If not, then boom, Jesus got a recipe.

To be clearer: if Jesus didn’t make the wine, Blackdom’s church folk wouldn’t drink it. They might not have, even if Jesus made the wine because they were sovereigns on sovereign lands; and God was “abba” (father). Blackdom was a conservative Afrotopia. The town enforced Temperance and homesteading required cooperation amongst Blackdomites.

Juneteenth at Blackdom had “No Booz” within a 3 mile radius of Blackdom Townsquare. It may have been a coincidence, but the infamous bootlegger Mittie Moore Wilson’s land was at the southern border of the 3 mile radius.

Unsuccessfully, Blackdom’s elders tried to contain the kids of the Jazz Age, we know how that went; #Harlem Renaissance. By the start of the Great Depression, Blackdomites had Juneteenth in Roswell, New Mexico 20 miles North.

#NoteToReader: Fitting; currently, the Roswell Correctional Facility is at the end of Chickasaw Road within 2 miles of the original Blackdom Townsquare.

Significance of Juneteenth

In 1915, Blackdom patriarchs were ministers, military men and Black freemasons who manifested a “Promised Land.” If I had to guess, Jesus probably would have wept for Joy as he witnessed his father’s promise in motion. And, he might have had a few more pressing things to do; since he was in town.

The Abrahamic Religions and teachings framed the grand narrative of Juneteenth for “Black” people. Non-believers in the faiths celebrated Juneteenth; and, the major Juneteenth celebrations were a military inspired affair. Authentically, Juneteenth was about God and the joy of his deliverance of Black People into sovereignty.

June 2020, during the early days of the apocalyptic pandemic shutdown, I couldn’t imagine joy, but found it on Juneteenth. White violence toward people under the conditions of “Americanism” and Blackness were subjected to the depravities of the #WhiteConsciousness. Worst of all, Juneteenth appeared to many as a platform to produce more trauma porn.

Sixty-Two Years of Freedom Be Celebrated At Blackdom 19th

Our sixty-second Juneteenth anniversary is scheduled to arrive at Blackdom, Chaves County, New Mexico, on Sunday, June 19th, 1927.

On that day, it is being arranged to have, instead of a jazz band to furnish music, a well-trained choir to sing the choicest of our “Plantation Melodies,” as well as some of the latest negro spirituals. There will be preaching of course whether you like it or not. That means by the very nature of the thing that there will be no booze in three miles of town and certainly none will be on the grounds if hoping will keep it away. In the plan, provision is being made to utilize every moment of time from start to finish in singing, praying, preaching, and lecturing on all important questions now agitating the minds of today.

Room will be made on the program for school children from anywhere and everywhere, this giving our boys and girls an excellent opportunity to read or declaim in public.

Everybody is hereby cordially invited to come and help swell the crowd. And don’t forget if you come you are under ten thousand and one obligations to bring your eats with you, if you think well of your appetites. Clinton Ragsdale will furnish barbecue, but this is a basket dinner.

Come on Sunday, June 19th, 1927, dressed in your Sunday clothes and with your baskets running over with the best eats you ever prepared. So Long!

Blackdom.

Significance of Juneteenth At Blackdom

#NoteToReader: Jesus was a guest of honor every Blackdom Juneteenth, as well.

Blackdomites were of an Ethiopianist tradition, most of whom believed in God’s promise. Googling “Jesus Wept,” I found Luke 19:41 (King James Version of the Holy Bible). “And when he was come near, he beheld the city, and wept over it.” I imagined he beheld Blackdom (the town) and wept once more. The duality of Blackness would evoke a peek into the distant future to say his name; Emmit Till c.1941.

One Black sovereign space wouldn’t stop the perpetual motion of Whiteness during the 20th Century, but it was a proof of concept for future generations. Most importantly, Blackdomites were homesteaders and earned exclusive rights to land with federally registered land patents.

Believers assume God and Jesus are omnipresent. Jesus could see the full 150 year continuum (1865 - 2015). In Blackdom, though, he would have seen joy c.1915. The day was celebrated in a semi-sovereign space; little separated Blackdomites from their God.

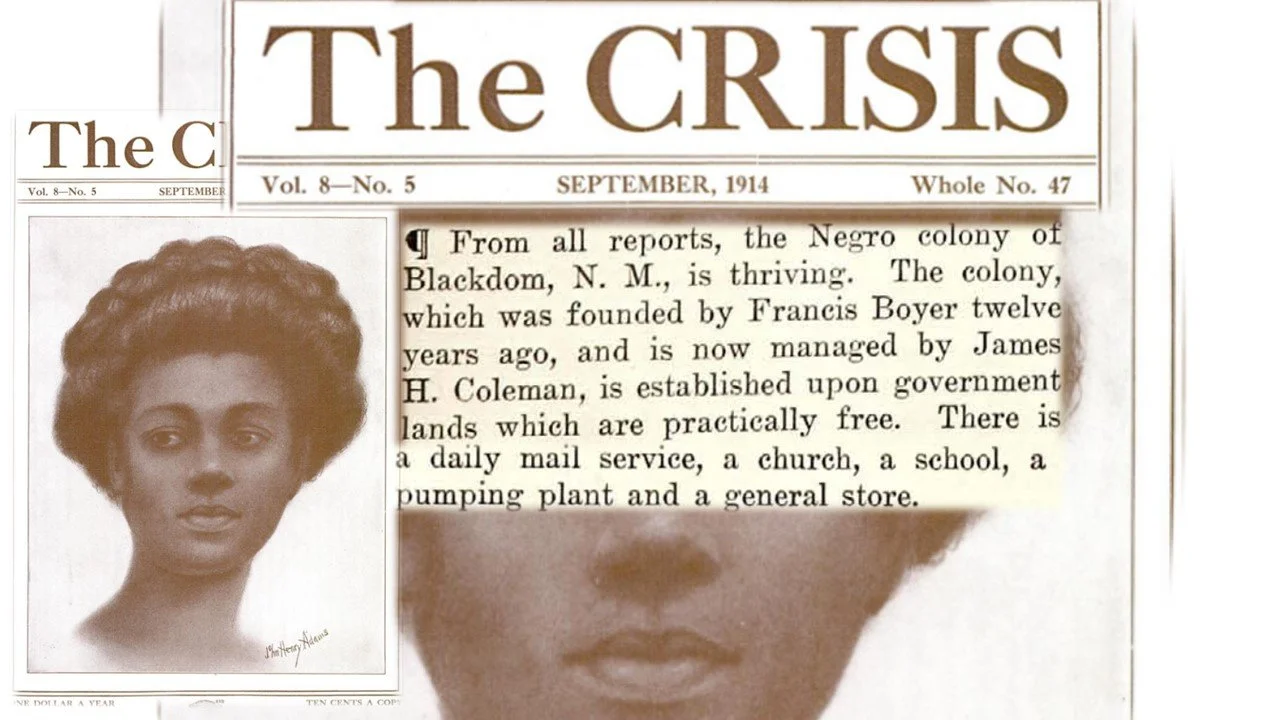

Image created by Timothy E. Nelson© The Crisis Magazine, September 1914, Vol. 8—No. 5

On June 10, 1914, Frank M. Boyer earned his second homestead patent for 40 acres using the 1909 Enlargement Act as assignee for Pernecia Russell and Mattie Moore. Blackdom Townsquare was under the legal authority of the May 20, 1862: Homestead Act that made it extra special.

Officially, the “Exclusive Negro Settlement” had land attached to their Afrotopic notions. Blackdomites employed Journalist Harold Coleman, one of Black America’s “Who’s Who” at the time, to project a rustic-bourgeois in The Crisis magazine. Coleman wrote: 500 Negro families (farmers preferred) to settle on FREE Government Lands in Chaves County, New Mexico. Blackdom is a Negro Colony. Fertile soil, ideal climate. No “Jim Crow” Laws. For information write JAS. Harold Coleman Blackdom, New Mexico

Harold Coleman was married to Anita Scott Coleman who was most known for participating in the Harlem Renaissance from Blackdom. “Black” Jesus would have felt the pride of Black folks at the peak of Afrotopia.

#NoteToReader: Similar to 2015, in the age of Obama and the era of post-racial-delusion, Blackdom’s Day of Jubilee, in 1915, was tainted by the virus of White supremacy; Birth of a Nation was a popular culture phenomenon, but on the Black side of town it was devastating. “Americanism” dominated popular culture, and Blackdom felt the first blows when “Black” and “White” kids in Roswell (20 miles north of Blackdom) had proxy fights during an age of significant racialization. Black folks experienced a similar “Americanism” at the start of the post-Obama era (2015-present) when political candidates projected Mexicans as “Rapists.” Black then, in 1915, Black men were the “Rapists” in the dank spaces of the White conscience; hence, King Kong.

Significance of Juneteenth; Blackdom, and a Roswellian Post-Script

In 1915, Mittie Moore Wilson, the infamous gun slang’n bootleg’n madame, started her homestead journey in Blackdom commons that year while running a bawdy business empire from 201 S. Virginia Ave. Close to Halloween c.1915, Mittie Moore’s Contempt of the Sovereign case before the newly created (1912) New Mexico Supreme Court ended with a ruling against her claim to sovereignty. After statehood, jurisdiction over bodies helped racialize the minds and incarcerate the “New Mexican” spirits. The “Black” nightmare became a reality in the newly incorporated State of New Mexico.

Non-believers had a lot to process mentally in order to maintain joy on the Black side of town. Believers had little worry and extended themselves even further, reaching out to some of the most racist people Southeastern New Mexico could muster.

A number of negros from the Blackdom settlement up the valley came to Artesia Saturday afternoon and put on a very creditable performance in the Corringhall that night. The receipts went to the building fund of the Blackdom Church. It is the intention of the troupe to give concerts at other places in the Valley.

Blackdomite believers (c.1915) had reached God’s sovereignty; and celebrated their God-given sovereignty by worshiping him. They also raised an offering to manifest the covenant on earth.

The “Black” revolutionaries of the Christian faith recognized the subversive power in joy. Believing oneself as spirit and body increased the capacity of people to endure the physical degradation, and nurtured mental as well as emotional resilience/intelligence. Believers and non-believers in Blackdom acknowledged God as part of their “Black” experience.

“Black” bodies possessed by “White” consciousness brought about sickness, pessimism and death. Non-believers couldn’t even trust a Ford. Thursday, December 30, 1915 the Santa Fe New Mexican [200 miles North on 285] reported, “‘Another Ford Goes Mad’ At Blackdom, ten [20] miles south of Roswell, the car containing Ross Miller, W.W. Hardin, and Tom Brown collide with a dagger….”

By Juneteenth of 1915, Blackdom was a thriving unincorporated “Exclusive Negro Town.” A rustic-bourgeoise of ministers, military personnel and Black Freemasons morphed into a landlord class of successful homesteaders. Possessing one’s self and land equaled a chance at God’s sovereignty. All Blackdomites were required to honor God’s laws of seedtime and harvest.

On Juneteenth of 1915, Immanuel would have been comforted because Blackdomites possessed the land patents and ruled their domain. Blackdomites solidified their sovereignty and were only accountable to God. Sovereignty ended on Thursday Jun 1, 1915, the Estancia News-Herald reported, “El juez federal William H. Pope ha abolido la oficina del comisario de los Estados Unidos en Blackdom.” Basically, the Ku Klux Klan and federal power nullified Black folks’ only sovereign space in New Mexico.

#JuneteenthAtBlackdom

Start of the #GreatDepression, Blackdomites maintained "in town."

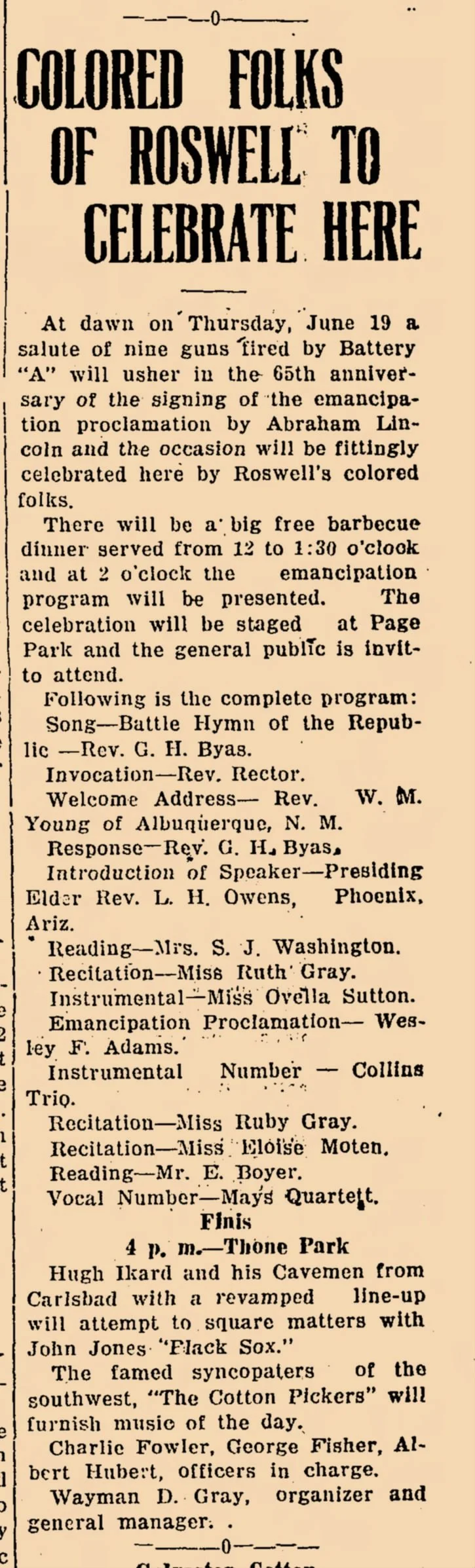

At dawn on thursday, June 19 a salute of nine guns fired by Battery “A” will usher in the 65th anniversary of the signing of the emancipation proclamation by Abraham Lincoln and the occasion will be fittingly celebrated here by Roswell’s colored folks.

There will be a big free barbecue dinner served from 12 to 1:30 o’clock and at 2 o’clock the emancipation program will be presented. The celebration will be staged at Page Park and the general public is invited to attend.

Following is the complete program:

Song–Battle Hymn of the Republic

Invocation –Rev. G. H. Byas

Welcome Address –Rev. Rector

Response –Rev. W. M. Young of Albuquerque, N.M.

Introduction of Speaker–Rev. G. H. Byas

Presiding Elder–Rev. L. H. Owens of Phoenix, Ariz

Reading–Mrs. S. J. Washington

Recitation–Miss Ruth Gray

Instrumental–Miss Ovelia Sutton

Emancipation Proclamation–Wesley F. Adams

Instrumental Number–Collins Trio

Reception–Miss Ruby Gray

Reception–Miss Eliose Moten

Reading–Miss E. Boyer

Vocal Number–Mays Quartett

Finis

4 p. m.--Thone Park

Hugh Ikard and his Cavemen from Carlsbad with a revamped line-up will attempt to square matters with John Jones “Black Sox.”

The famed syncopaters of the southwest, “The Cotton Pickers” will furnish music of the day.

Officers in charge Charlie Fowler, George Fisher, Albert Hubert organizer and general manager Wayman D. Gray, organizer